Album

The architect drew up his plan To realize the dream of man. The palace rose - a work of art To which the hand of god was part. The dome that crowns the palace wall Attracts the light of stars that fall. The lancet windows rising high Reflect the beauty of the sky.

The golden dawn has shed its light On domes of tiles and colours bright And towers rise - a match to bird From where appeals to pray are heard. Amazing beauty stems from walls Of mosques where people hear the calls.

The hills of Afrasiab are lifeless (Afrasiab is the name of the ruler of Turan, a legendary character of ancient oriental epics; in the 17th - 18th centuries common talk associated the name with the ruins of a deserted ancient town). The town that declined long ago is buried beneath a greyish-yellow layer of loess. A vast graveyard, that is almost 2,000 years old, stretches southwards. Two straight highways intersect the site of the ancient town. Numerous paths meander among the hills and ravines. Every year archaeological excavations reveal ruins of the ancient town.

The site of the ancient and medieval town of Samarkand has been deserted since the 13th century. Later Samarkand appeared on this plot - one of the most ancient centres of civilisation and culture.

Samarkand, the capital of ancient Sogdiana (the area stretching along the upper and middle course of the river Zarafshan in the heart of Central Asia) appeared in the middle of the first millennium В. C. at the time of the Akhemenid State of Cyrus in Iran. Its walls were besieged by Alexander the Great (the 4th century В. C.). Reference of Samarkand can be found in ancient sources (Arrian, Quintus Curcius Ruf, Strabon, Plutarch et al.).

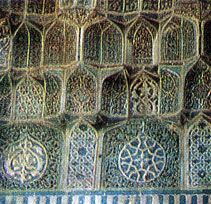

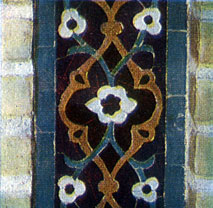

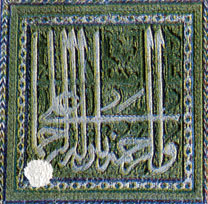

A fragment of a corner column of a portal. The technique of carved glazed terracotta. The last third of the 14th century

Time and again Samarkand was rased, pillaged and deserted. Nevertheless, each time the city was raised from the ruins, rebuilt and beautified with new edifices; its bazaars were packed with gay and noisy throngs.

At the turn of the 8th century the city was conquered by Arabs; in 1220 A. D. it was rased by the hordes of Genghiz-khan, after which life in Afrasiab came to a standstill. However, by degrees it revived in the former suburb (rabad), now known as the old town, to the south of Afrasiab.

From the 14th century Samarkand was the capital of Timur's (Tamerlan's) vast empire that stretched over entire Central Asia, Iran, Afghanistan, the Middle East and a large part of India.

During the rule of Timur ("the iron cripple"), who longed to convert Samarkand into "a radiant spot on the earth", countless riches were brought to the city. Many buildings were put up, whose massiveness and magnificence were missioned to glorify the power of the Emir of the feudal empire.

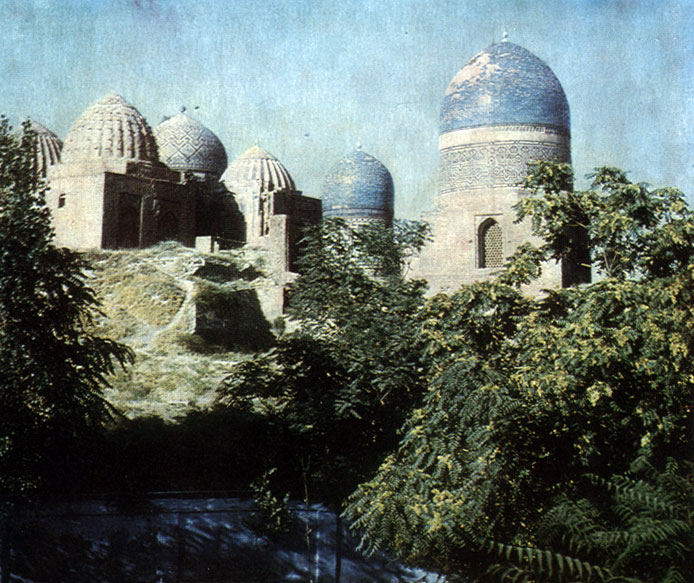

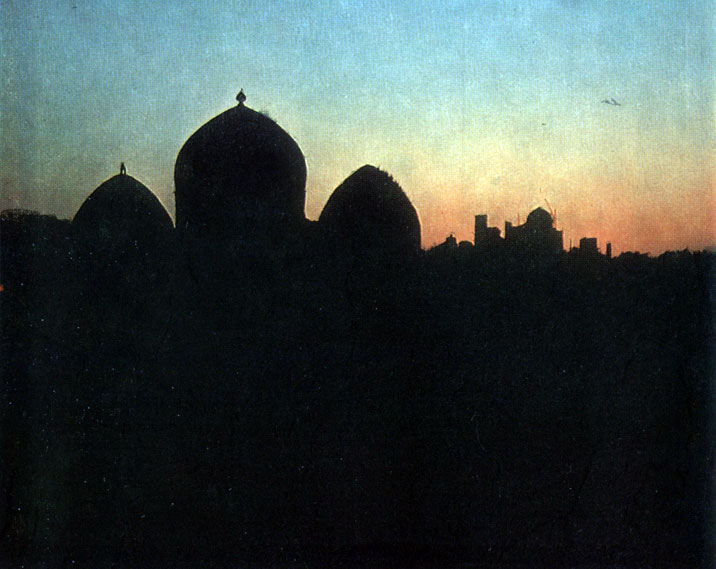

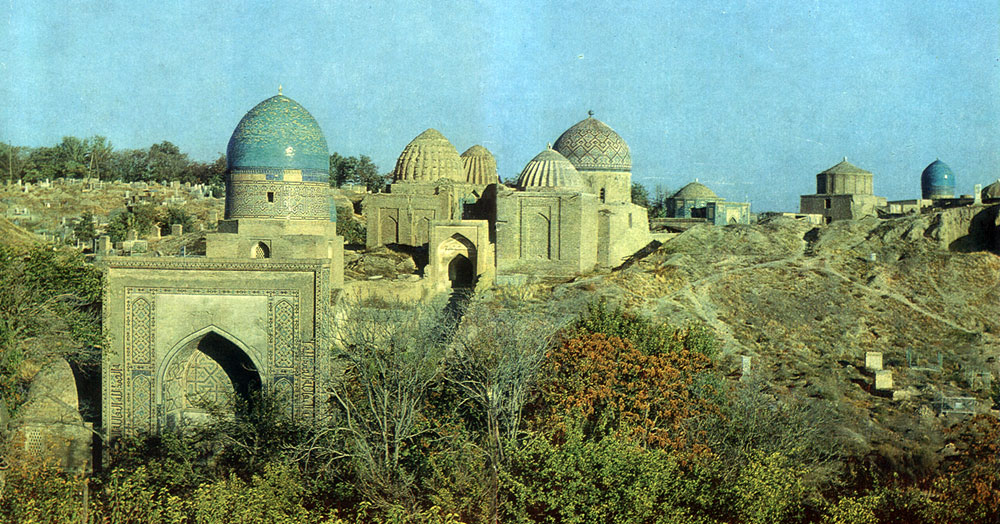

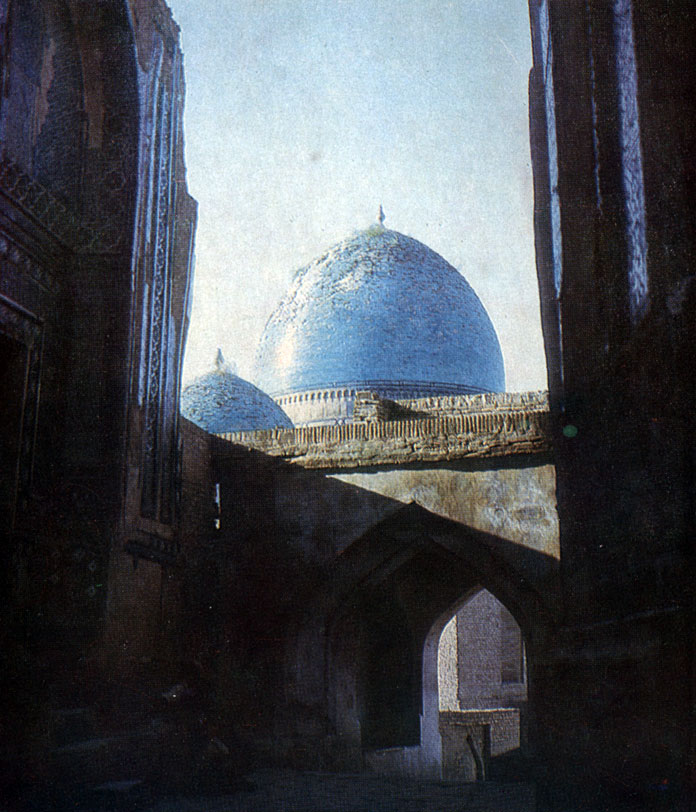

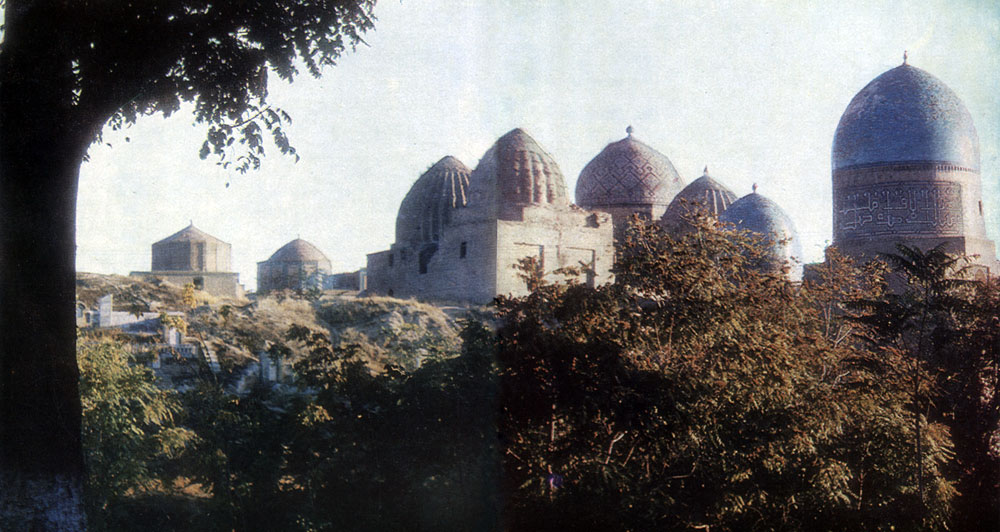

One of the architectural creations of that time was a group of mausoleums in the Shahi Zindah country ensemble, that was located in the southern outskirts of Afrasiab among scorched hills and graves. In contrast to the waste the royal necropolis stands as a miracle, full of colours and life.

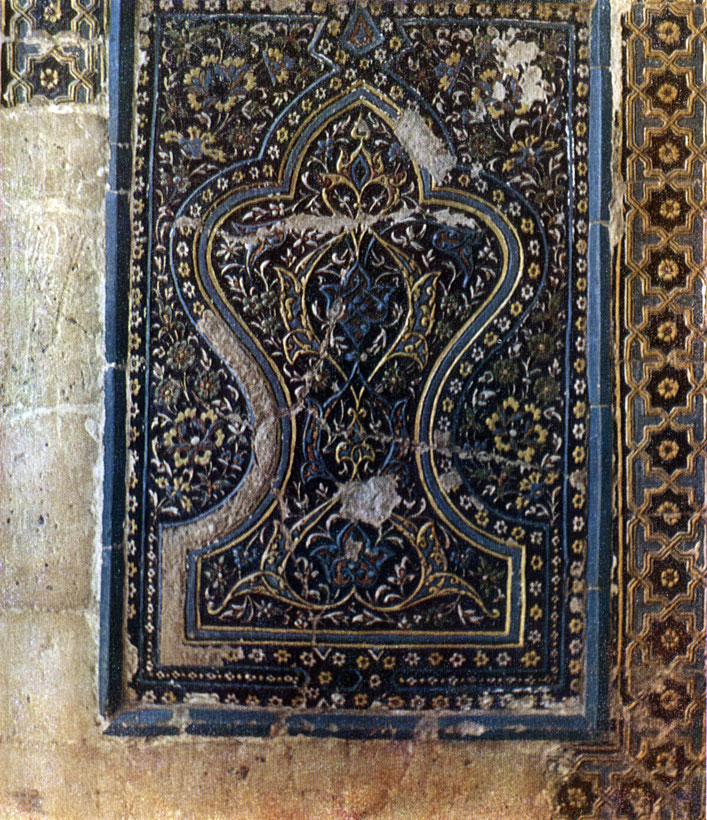

The base of a corner column of a portal of Shadi-Mulk-aka mausoleum. The technique of carved glazed terracotta. 1372

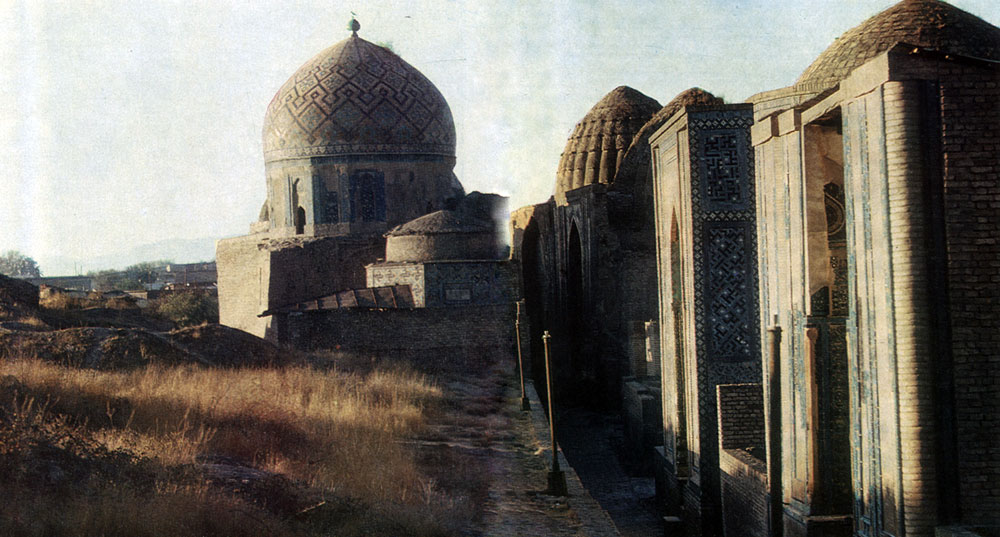

This "pearl of Samarkand" (as it is commonly called) includes a chain of small but wonderfully harmonious and original mausoleums. It stretches along the site of the ancient town and spans the swollen crest of the rampart at its foot.

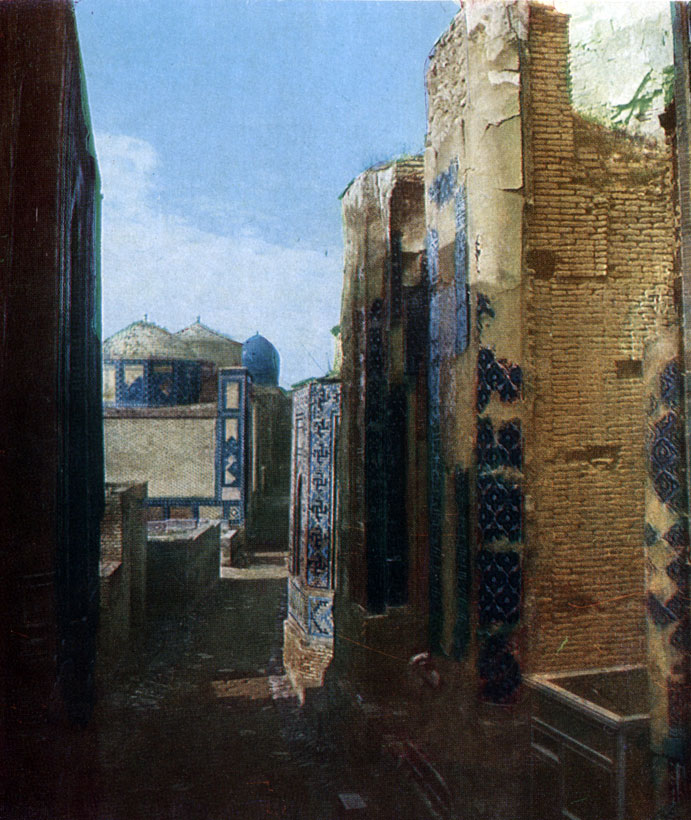

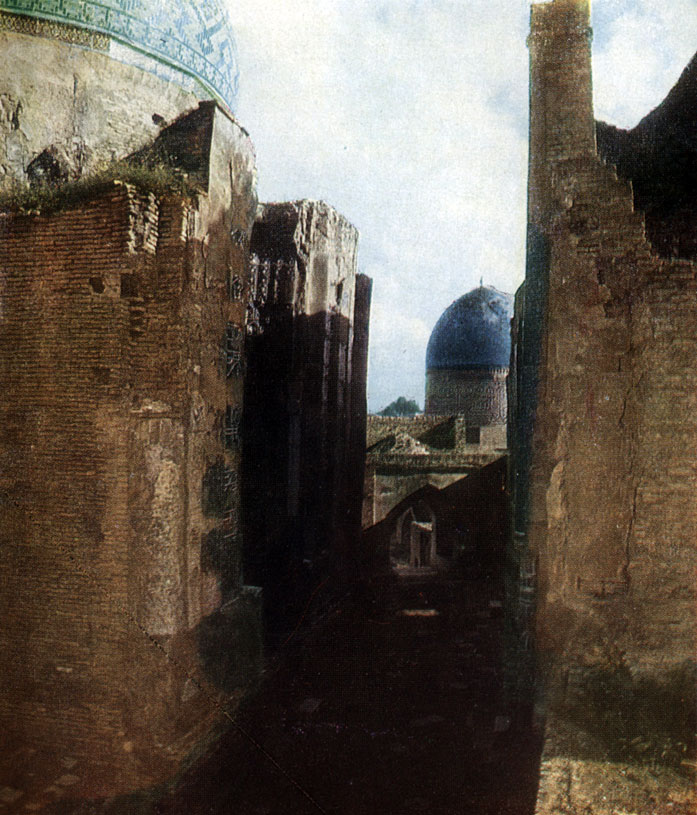

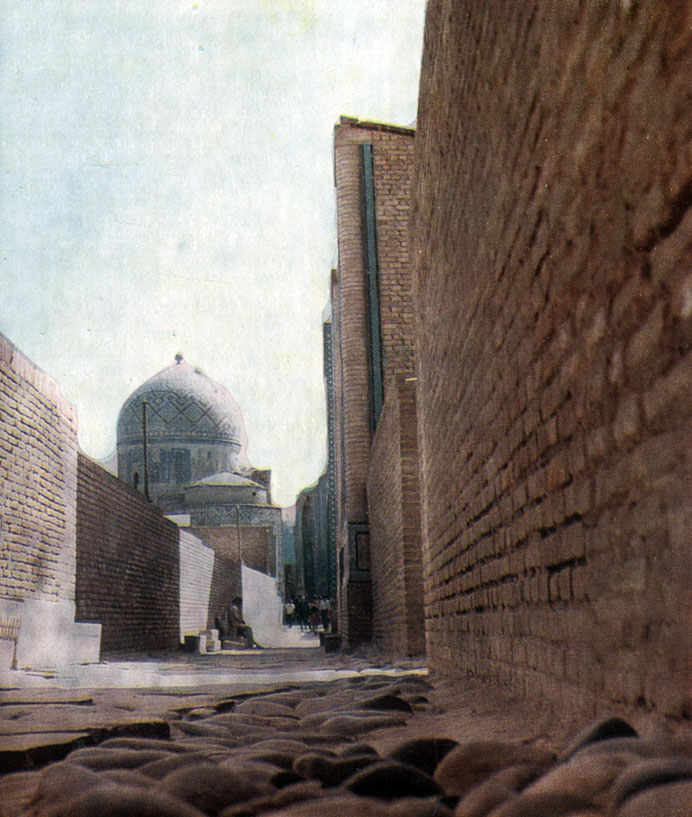

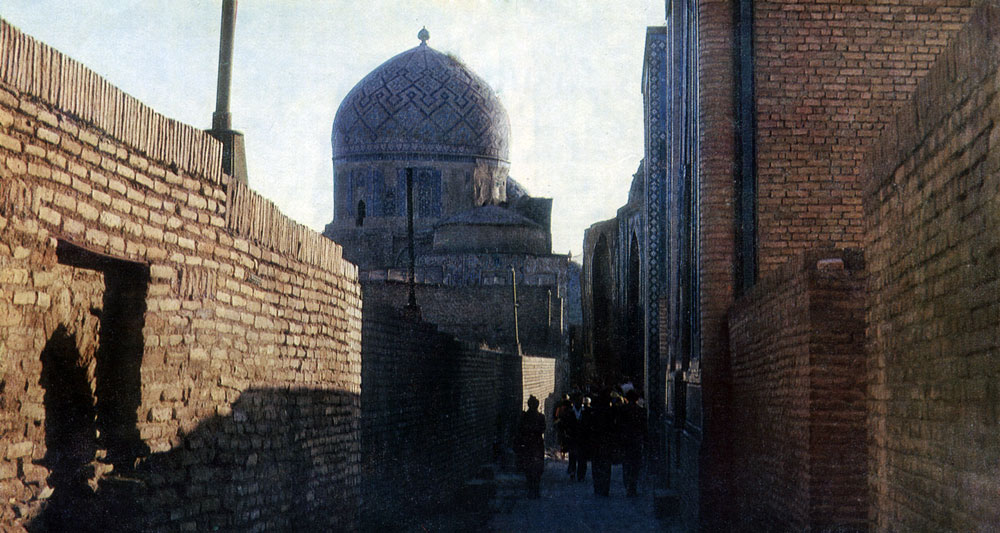

The Shahi Zindah ensemble is unique and inimitable in its beauty. The passage with close-built edifices, that spans the crest of the ancient walls of Afrasiab, resembles the narrow streets of Central Asian feudal towns in the Middle Ages. It was ascertained that the monument was built within the precincts of a close-built residential district of Samarkand in the 11th century and its layout iterated the historically established topography of the neighbourhood.

Nowhere is the motion of time sensed with such verity as at the Shahi Zindah ensemble. The sense of intimacy and submergence into times long past is not only created by the complete isolation of the monument from the modern city with its noisy streets, light, and gay crowds, but by its composition, the chamber form of the structures locked in small courtyards.

As recently as a century ago this amazing creation of people's genius was shrouded with mystery and legends, of which it was forbidden to get to the bottom. The way was barred by mullahs and sheikhs, who were zealously careful to see that no European had access to this popular worship ensemble for centuries, and who manifested no real interest in the masterpieces of art. Pilgrimages to Shahi Zindah used to substitute the "khadj to Mecca" (pilgrimage to the reputed birthplace of Mahomet).

Nevertheless, the Shahi Zindah ensemble is of great significance as a source of knowledge of the ancient culture of the peoples of Central Asia. It is a brilliant embodiment of conception of the art of building, aesthetic standard, construction and designing. The ensemble was built in the course of almost nine centuries (the 11th - 19th centuries) and comprises more than 20 edifices (of different periods) that remain on the surface alone. They not only represent the architecture of mausoleums in Samarkand but the formation and development of the school of architecture of Mavara al-Nahr as a whole, the monumental, decorative and applied arts and their evolution in Central Asia.

The formation of the ensemble over such a long period of time, its destruction and desolation, coupled with changes in the course of rebuilding at all stages got mixed up with the complex fate of the city, as if embodying the latter's main social and cultural manifestations.

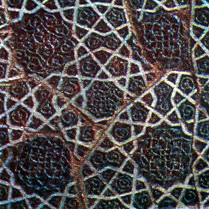

Carved glazed terracotta. A 14th century fragment

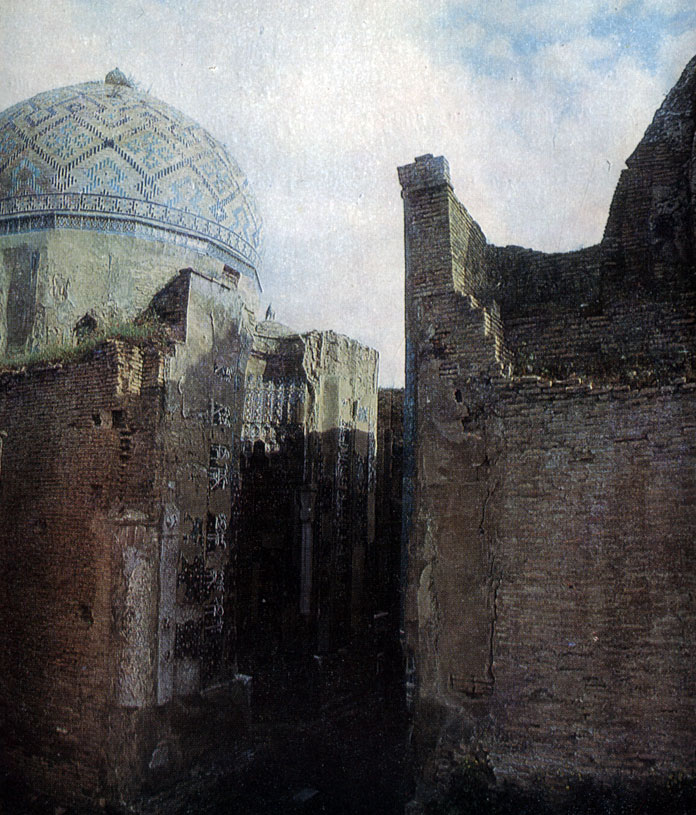

Shahi Zindah is the only architectural relic in Samarkand that reflects the almost 25 centuries-old history of the city, including the cultural layer of Afrasiab. A 19th century traveller to Samarkand recounts his impressions of Shahi Zindah in the following terms, - "Shah-Sindeh (Shahi Zindah), the most magnificent building in Samarkand, is completely destroyed and one has to approach it with great caution for fear of being crushed under the cracked columns or vaults". It was also a kind of public and educational centre. The Tamgach Bogra-khan medresseh (a higher Moslem ecclesiastic school) was located there in the 11th - 12th centuries. It was one of the biggest in Samarkand, where, according to written data, secular sciences were taught.

The first European researchers of Samarkand in the 19th century (N. Khanykov, M. Solovyov, A. Lemann, A. Vamberi et al.) designated Shahi Zindah as follows, - "Timur-lyang Palace", "the residence of the great conqueror" and "Timur's summer residence" and even a monastery. So beautiful and life-asserting was its aspect that it never occurred to anyone to call it a mausoleum. N. Khanykov wrote, - "Of the buildings located beyond the city we recollect one of Timur-lyang's palaces. It is situated in the northern part of the city and is called Khozreti-Shahi-Zindah... The remains of mural decorations, comprising porcelain mosaic for the most part, are very beautiful and magnificent... It is best viewed from the south as from there the eye embraces all the buildings of the Palace in perspective, among which there is a wide and splendid staircase..."

In Soviet times the Shahi Zindah ensemble, just as all the architectural heritage of Samarkand, is under the protection of the State. It was almost completely studied and restored by the end of the 1970s. The Shahi Zindah ensemble is the only historical, cultural and artistic treasure-house of medieval Central Asia, possessing various kinds of buildings (mausoleums, mosques and even medressehs), engineering and designing solutions, decorative and facing techniques (mosaic, majolica, carved terracotta, painting on ganch, carving on wood and marble).

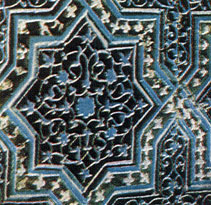

A fragment of multi-coloured glazed majolica. 14th century

The first buildings of the ensemble appeared at the crossing of the town canal and old street that was paved with slate flag-stones, that stretched eastwards from the main water distributor at the Kesh gates. The Kussarn ibn Abbas complex (the first half of the 11th century) was erected on the east side of the street, that was the chief ideological centre of the necropolis. One of the oldest medressehs known in Samarkand was put up opposite it on the west side. It was built by Tamgach Bogra-khan, a Karakhanid ruler, in 1066. The first tombs of Samarkand nobility were erected to the south along the same street up to the wall of the fortress. The ruins of these structures were dug up for the erection of mausoleums in the 14th - 15th centuries.

In the course of centuries both the appearance of the ensemble and its purpose changed. After the Mongolian invasion (in the 13th century) Afrasiab was neglected; Samarkand extended over the territory of Afrasiab's suburb (rabad) that comprises the old part of present-day Samarkand. In the 14th - 15th centuries the "sanctum", which was as popular as in earlier times, became the country family graveyard of the Timurids. The highest point of construction and monumental art in the ensemble was reached in the epoch of Timurid and the Timurids in the 14th - 15th centuries. At that time mausoleums were erected there for high-ranking clergymen and statesmen. As a result of change of the ruling dynasty and transfer of the capital to Bukhara in the 16th - 19th centuries the ensemble was neglected and no more magnificent tombs were erected. In the main, monumental building was concentrated in Bukhara. The small modestly decorated memorials for worship, that were put up in these centuries, did not change the appearance of the ensemble to any great extent.

A fragment of carved-glazed terracotta. 14th century

This unique ensemble, that was built in the course of nine centuries (at the height of political and cultural rise of Samarkand in the 11th - 12th and 14th - 15th centuries in the main) gave a memorable description of the skill of popular masters - architects, ceramists, ornamentalists, calligraphers, carvers on stone and wood, and painters of different periods, whose names are unknown to us for the most part. The edifices of the Shahi Zindah ensemble were destroyed to a considerable extent during the ages. Here and there intermittently there are closely grouped mausoleums or wastes. The remaining structures mostly date from the 14th - 15th centuries; many buildings of that period have disappeared from the face of the earth. Monuments of the 11th - 12th centuries were almost completely ruined and only archaeological research in 1950 - 1960 permitted to revive with exactness the history of how the ancient necropolis was built stage by stage and reveal the buildings that do not exist today. The southern part of the ensemble, which stretches along the external slope of the rampart of Afrasiab leads to the thoroughfare at its base; the northern part seems to have grown into the lifeless hilly surface of the old graveyard. The general layout of the monument along the passage is divided into three groups conditionally - "the lower group", "the middle group" and "upper group" of edifices, all of which are connected by arch-and-cupola structures (chartak). The fourth group of isolated buildings, comprising the most ancient Kussam ibn Abbas ensemble, is located in the north-east.

Before Soviet rule this "sanctum", that was jealously protected by the clergy in Samarkand, was not accessible to Europeans. Various religious ceremonials, including "ziarat" - a formed practice of worshipping sacred places, which was elaborated during ages, were held there. Offerings were brought and intercession was implored of Allah.

Kussam ibn Abbas (Shahi Zindah - the living monarch) - the most intimate associate and cousin of the Prophet Muhammed - was one of the first preachers of Islam in Central Asia. The name of the "fighter for the faith" is shrouded with legends. Written sources of the 19th century disclose that Kussam really existed as a personality. As far back as the second half of the 7th century A. D., i. e. before the occupation of the towns of Central Asia by the Arabs was completed, Kussam came to Samarkand (or Merv, according to other sources) with the first armed forces of Moslems, where he died. Legend would have it that his army was routed by infidels while the Moslems were praying. However, Kussam was saved by a miracle - a niche for worshipping (mikhrab) appeared before him and so he hid himself there. According to a more popular legend, Kussam ibn Abbas lowered himself into a well (or cavern), where he lives to this day (a living monarch).

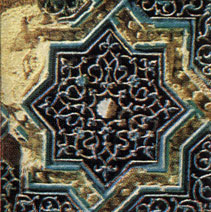

A detail of a border of the main fagade of Emir Burunduk mausoleum. Carved glazed terracotta. 14th century

Popular imagination interwove wonderfully with facts. The introduction of a new set of Islam doctrines among the pagans of Central Asia met with stubborn resistance at first. Different versions of legends concerning Kussam present themselves as a reflection of real dramatic events that took place in the southern outskirts of Samarkand in the 7th century, where "the fighter for the faith" (gazy), who was revered by Moslems for his relationship to the Prophet, was "martyrized" by those who were still in opposition to Islam.

Circumstantial evidence of this is the name of the irrigation ditch (aryk) Obi-Mashad (mashad - place of martyrdom, violent death), that flows near the Shahi Zindah ensemble at the southern foot of Afrasiab. Four centuries later (in the middle of the 11th century) a memorial ensemble was put up in honour of the preacher of Islam, who had been canonized by that time.

Excavations, carried out in the burial-vault of the Kussam complex, where a gorgeous majolica tombstone was placed in the 1380s, disclosed that there are no signs of Kussam ibn Abbas' remains there. Though Kussam's real grave was not discovered (the earliest tombs of Moslems were modest and without any splendid tombstones), it is supposed that his place of burial was somewhere in the south of Samarkand or beyond the city at the foot of the walls where the Obi-Mashad flowed. Making sham graves, the artificial removal of "sanctums", and setting them up in different places simultaneously - was widely practiced not only in Central Asia, but throughout the Moslem Orient.

Such is the pre-history of the construction of one of the biggest memorials of the Middle Ages.

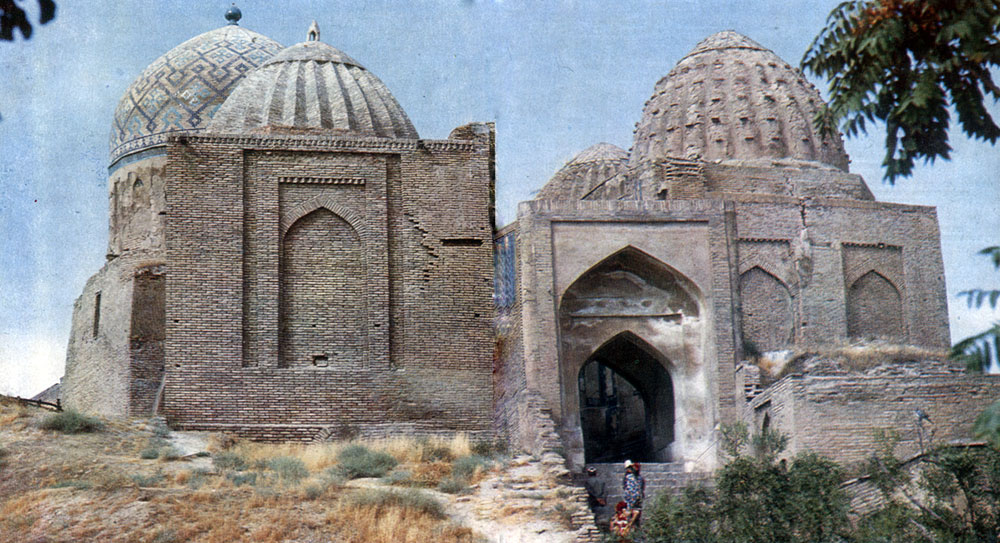

The Kussam ibn Abbas complex - the oldest part of the Shahi Zindah ensemble, that was built in the south of Samarkand in the first half of the 11th century, comprises a compact historically established group of intercommunicated structures (gurkhana, ziaratkhana, underground chillyakhana, semi-subterranean mosque and a minaret). The external fagades of the complex are almost one-third "grown" into the ground, architecturally not worked out, and void of decoration. Nevertheless, the general appearance of this group of buildings is very striking. The conglomeration of edifices of different size, decorated with brickwork of greyish-yellow texture with traces of rebuilding and restoration - is merged into a single whole complex.

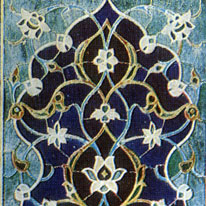

A fragment of facing of the turn of the 14th century. Sets of mosaica compiled of glazed tiles based on silicate

Unlike the monotonous external faсades, the interior of the complex presents a vivid picture of stratification of buildings of different kinds of sub-cupola systems, ornamentations, numerous plaster decorations and laying.

Studies show that the initial central part of the ensemble had a complex layout with an unique two-layer solution, which remains to this day. The complex composition of the premises (gurkhana, ziaratkhana, underground chillyakhana, subterranean mosque and minaret) was predeterminated by the function of the ensemble and conditioned by the ritual of worshipping "holy places", that was worked by Islam in the 11th century. In the 11th - 13th centuries the Kussam complex was independent of the other part of the ensemble and had two entrances (northern and southern). In the 14th century after the upper chartak was erected at the 11th century minaret, that combined the ancient "sanctum" and ensemble of buildings along the north-south path, the main thoroughfare that led the pilgrims to the Kussam graveyard (mazar) was where tourists pass along nowadays. The base of an 11th centufy minaret (a turret on a Mohammedan mosque from which the muezzin calls worshippers to prayer) can be seen at the entrance to the Kussam complex. Besides the Kussam tombs (gurkhana), it is the only pre-Mongol structure in Samarkand to reach our days intact. Its shaft was bricked up with masonry of later periods (the 14th - 16th centuries) for ages; the base and upper rotunda are all that remain of it. The minaret is 12 m high. Its cylindric shaft is placed on a tetrahedral prism, whose socle, frontage and north side intersect a deep arched niche. The rectangular sides of the prism and border of the arch are encompassed with plaited bricks in relief, that are typical of the 11th - 12th centuries. The tympanum of the arch and shaft are decorated with figured brickwork of slipknot form.

A fragment of facing of the turn of the 15th century. Sets of mosaic made of glazed tiles based on silicate

A beautiful carved-wood console of pre-Mongol period remains in the Kussam complex, that once supported the plane roof of a semi-subterranean room next to the ziaratkhana. These are composite friezes, faced with Cufic epigraphs, floral decorations, and a huge console beam projecting out of the wall, that was covered with intricate carving. Its clear extremity, just as most of the synchronous consoles, was carved with the stylised head of a ram - an ancient popular symbol of prosperity in the East.

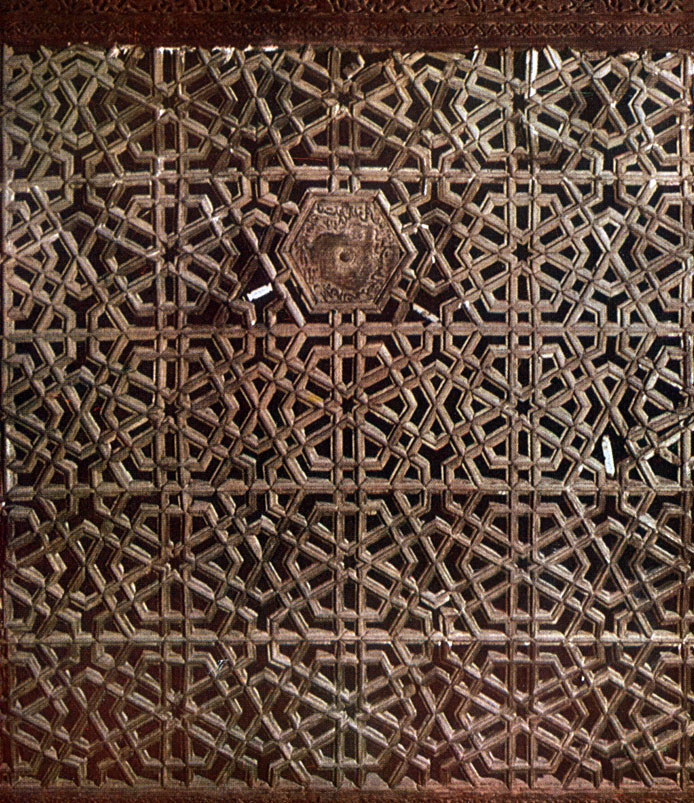

The Kussam complex has preserved other monuments of carved wood - a composite open-work wooden trellis (panjara) in a through niche of a tomb (the 14th century) and a door of masterly work of the 14th century, that leads from the ziaratkhana to a through chamber (mionkhana) in the middle.

The massive elm (karagach) folding door at the aperture of the chartak in a closed passage of the complex was made in the 14th century. It is covered throughout with dainty bi-plane carving, that was once inlaid with ivory.

"The doors of heaven, open to the people" - such is the inscription on the right side of the door, and on the left side is the name of the master who made the door "the work of Sayid Yusuf Shirazi". The date is inscribed below - 807 hejira (1404 - 1405). After passing through a closed passage one reaches the latest and grandest building of the complex - a big mosque put up in the 15th century on the remains of the walls of a semi-subterranean structure with carved console of the 11th century.

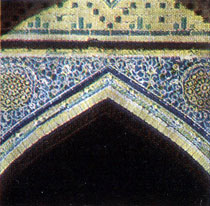

The rectangular layout of the mosque stretches from east to west. A polychrome mosaic panel of starshaped design floors the light, clear interior faced with ganch and traces of painting.

The most impressive is the niche for worship in the west wall, facing Mecca. The rectangular frame, encompassing the niche, is interwoven with epigraphs (quotations from the Koran and religious quatrains).

The aperture in the north-eastern corner of the mosque leads to the most ancient part of the ensemble - the Kussam ibn Abbas mausoleum, consisting of the ziaratkhana, gurkhana and an underground chillyakhana. In the main this group of edifices has remained since the 11th century. Nevertheless, its original aspect has undergone a change as a result of repeated reconstruction and alterations. In the 1330s the ziaratkhana was rebuilt. The cupola above the 11th century walls was erected anew and faced with carved tiles of greenish-blue, white and greyish tones.

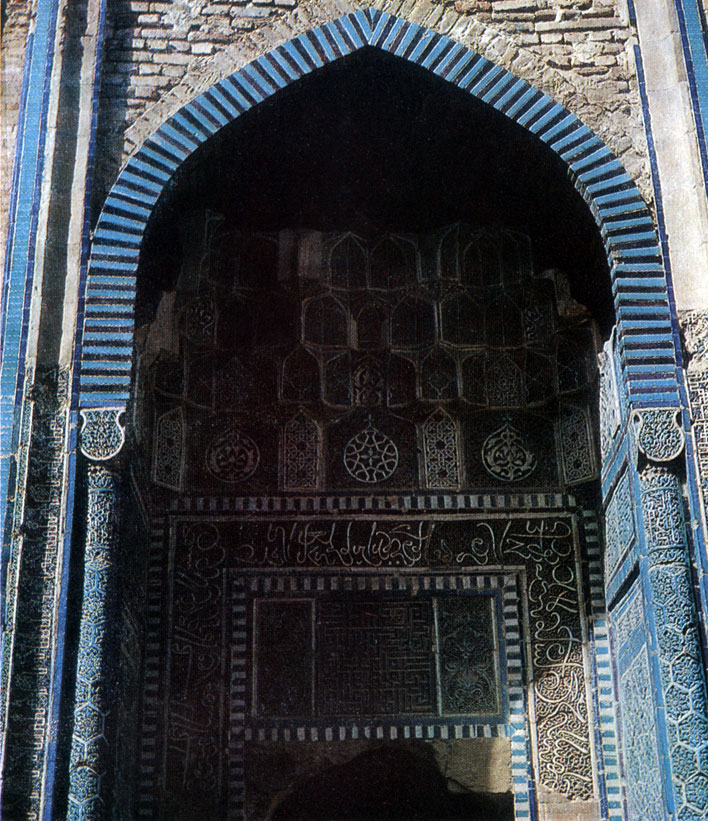

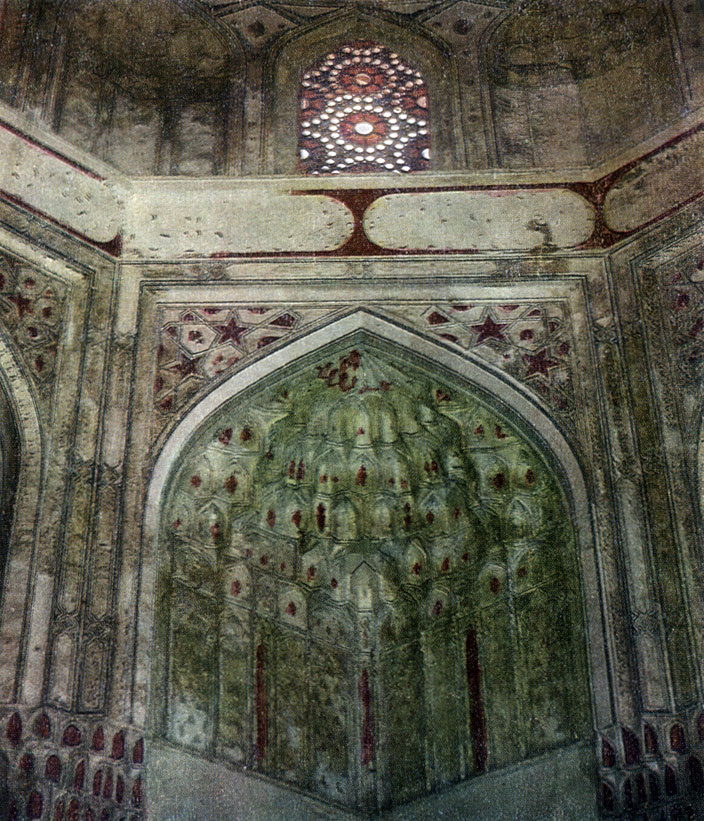

Decorative ceramic stalactites in the portal niche of the 1361 mausoleum. The technique of carved glazed terracotta

In the south-western corner of the arched pendentive ( the crossing towards the cupola) the date 735 hejira (1334 - 1335) of reconstruction is inscribed with a floral design. At the same time the ganch walls were adorned with polychrome paint. In 1959 - 1960 the dilapidated cupola was restored by Soviet masters after the old model. The well-preserved blue panel at the base of the walls of the ziaratkhana, that was composed of hexahedral slabs with polychrome and mosaic medallions in the centre and a mosaic bordure along the edge, appeared in the 15th century.

The stepped ceramic tombstone was placed in the burial-vault under Timur's rule in the 1380s. It is a masterpiece of Central Asian ceramics. The sides of the steps were faced with majolica plates in relief. A delicate gilt floral design of light tone was interlaced with quotations from the Koran and religious quatrains. There is an epitaph to Kussam ibn Abbas with the date of his death - 57 hejira (676 - 677) on the upper face plane of the tombstone.

There was a huge building with an open courtyard opposite the Kussam complex. Excavations of its walls and foundation were carried out at the end of the 1960s and beginning of the 1970s. The structure is identified with the medresseh of Tamgach Bogra-khan, a ruler of Samarkand of the Turkik-Karakhanid dynasty. According to written sources, it was put up at the Kussam graveyard in 1066 A. D. It is the oldest medresseh known to have existed in Central Asia. The remains of the walls and portal at the entrance to the medresseh with facing of paired ground bricks and bent-shape bricks are visible at the base of the prop wall to the south of the Emir Burunduk mausoleum.

The masonry of the walls of other 11th - 12th century buildings was cleared along the path of the ensemble within the boundary of the rampart of Afrasiab. They were gorgeously faced with carved unglazed terracotta. At the turn of the 13th century the Mongols destroyed Samarkand. Afrasiab was abandoned. Most of the 11th - 12th century structures were neglected. The revival of the necropolis began in the 14th century. New portal-and-cupola tombs were erected in place of the 11th - 12th century structures. Their decoration differed to a great extent from the facing of edifices put up in the 11th - 12th centuries. Instead of the carved unglazed terracotta of the old buildings new facing appeared - multi-coloured glazed tiles. Building in the ensemble was carried out on a wide scale under Timur's rule (1370 - 1405). Samarkand, the capital of the empire, was to outshine other towns and cities in the East. The most skilful masters, architects, artists, scholars, poets and musicians were brought to Samarkand from other countries. Material values were concentrated there as well.

Mosaic tympanum (a decoration above the arch) of the third chartak. The turn of the 15th century

Shahi Zindah, the main necropolis of the city, assumed a new aspect. The old pre-Mongol ensemble was reconstructed; the ruins of the 11th - 12th century buildings were pulled down and memorials were erected in their place with splendid multi-coloured glazed facing. A number of mono-cellular, portal-and-cupola tombs were built in the same style, resembling each other in composition, architecture and colouring of the ceramic ornamentation. Each edifice was single in architecture and decoration. The mausoleums of men of the world dominated and exceeded the Kussam complex in decorative splendour. 12 more mausoleums with mono-cellular tombs of various periods were discovered in the ensemble. They supplemented the mono-cellular mausoleums developed in Mavara al-Nahr and gave a clearer idea of all the stages of the construction of the Shahi Zindah ensemble in the 14th - 15th centuries.

The buildings of the 14th - 15th centuries are divided into groups close in style on the basis of typical features. Pertaining to the first group are tombs of the first half of the 14th century, that were erected in pre-Timur times at the crossing of the west and south highways to the north of the Kussam complex and Tamgach Bogra-khan medresseh. These include the Khodja Akhmad mausoleum (the 1340s), that was the last link in the chain of structures in the north of the ensemble, and the 1361 mausoleum built on the northern side of the highway, blocking the way to the west. Both monuments are mono-cellular, portal-and-cupola edifices, whose development is perceived in the buildings put up in the ensemble in the 14th - the first half of the 15th centuries. The artistic value of the tombs is evidenced by the decorative racing of the external and internal (in part) walls of the mausoleums, that was executed with carved glazed terracotta and painting on ganch. The carved clay decoration of the buildings was inherited from oriental architecture of pre-Mongol times. In the 14th century this kind of decoration appears in a combination of carving and polychrome glaze. Both monuments resemble each other to such an extent as to technique and nature of the facing that one can assume they were erected by one and the same master. The name of this ceramist - Fakhri Ali, who faced the Khodja Akhmad portal, is inscribed in a figured leaf of a floral decoration. The absence of his birth-place testifies that he was born in Samarkand.

Carved glazed terracotta. A detail of the facing. 14th century

In the 1360s - 1380s a number of tombs were erected along the south highway at the rampart in Afrasiab. The further development of the mono-cellular memorials in Mavara al-Nahr was coupled with the perfection of their ceramic facing. One of the oldest of these structures was the mausoleum of Timur's niece Shadi-Mulk-aka (1371 A. D.), that was constructed from the ruins of the mausoleum of one of Timur's military leaders Emir Khussein (more widely known as the mausoleum of his mother Tuglu-Tekin (1375 A. D.). In 1376 the Emir-Zade tomb was put up to the south of the Shadi-Mulk mausoleum; in the north there were burial-vaults of unknown persons, that were built at some previous time, whose bases were set open on both sides of the passage in the 1960s.

Three monuments, that have remained as a whole, give a clear idea of the aspect of this group of buildings. All three tombs have a common volume and layout. Ribbed cupolas crown a small cube; a splendidly decorated П-shaped portal stands at the main facade. Just as in earlier periods there are small burial-vaults in the subterranean part of the mausoleums. The material used for facing changed in a short while. In the Shadi-Mulk mausoleum carved glazed terracotta prevailed along with painted polychrome majolica (a new kind of facing) that only began to appear; the Tuglu-Tekin mausoleum (erected four years later) was decorated with both carved glazed terracotta and majolica. The Emir-Zade mausoleum was chiefly decorated with majolica. The development of building and facing is perceived in the tombs erected in the 1380s - 1390s. Three burial-vaults - a mausoleum created by Usto Alim-Nesefi (a Karshi master), the Unnamed-2 mausoleum with one portal and Emir Burunduk mausoleum - remain to this day on the south side of the passage. Instead of the single dome of earlier mausoleums, the cubic base of these was crowned with two cupolas (those of Unnamed-2 have not reached us).

Marble fretwork. A fragment of a tombstone. 14th century

Carved terracotta was supplemented with painted majolica in relief with coloured floral and epigraphic ornamentation. The blue tiles were brightened up with thin gold, red and white angobe painting on glaze. Though the intricate Arabic inscriptions are illegible for the most part, they beautify the majolica plates. The Shahi Zindah ensemble assumed its ultimate aspect at the close of the 14th - turn of the 15th centuries within the walls of Afrasiab. The axis of the north-south passage was rebuilt; a new axis in the west (along the highway leading to the Iron Gate, formally called the Kesh Gate) that became known as "the west passage", came into being.

The monuments of this next (as to chronology and style) group of buildings retained their previous volume and layout, though they were more symmetrical. The external frontage of the buildings, principally the portals, were faced with mosaic. The inside was covered with polychrome and gold painting on ganch. The inner premises became more spacious and enlivened in comparison with the ungainly interiors of the tombs built in the 1370s - 1380s. The mausoleum of Timur's sister Shirinbek-aka in the middle of the ensemble, the Tuman-aka complex (the mosque, mausoleum and cell), built in 1405/1406 on the instruction of Timur's wife - "the junior mistress" of his harem - Tuman-aka in the northern part of the ensemble and group of monocellular mausoleums along "the west passage" - are related to this group.

The Shahi Zindah ensemble was completed under Ulughbek (1409 - 1449).

Mosaic border, made of a set of carved glazed tiles based on silicate. Turn of 15th century

The chief work of architecture and layout of that period embraced the entire southern slope of the sight of the ancient town; nevertheless, some buildings appeared in the central group of the ensemble as well. The buildings put up under Ulughbek did not iterate the mono-cellular tombs of the 14th century; new art and work of building were exercised along with original layout and composition.

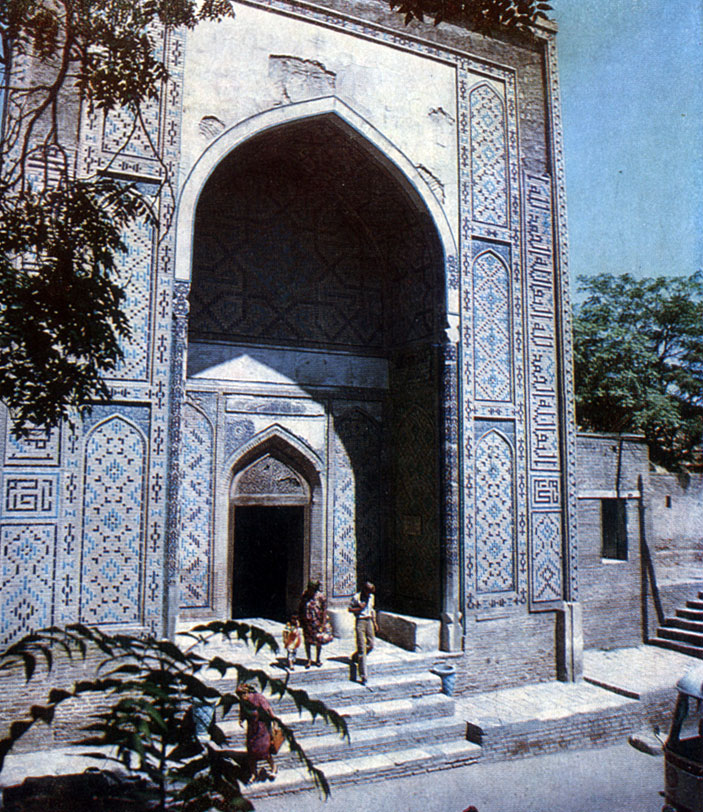

In the 1430s "the west passage" - the only way connecting the necropolis with the town in the 14th - early 15th centuries - was insignificant. The southern way to the ensemble became the main thoroughfare. It was of special importance after Ulughbek founded his observatory in the 1420s - 1430s, to which a country highway led along the southern outskirts of Afrasiab. In 1434/1435 a monumental domed portal was erected at the entrance to the ensemble with a winter section and premises for domestic work. The area next to the ensemble across the way was laid out to a common plan. In the 15th century a common, spectacular composition of architecture and layout was created at the steep slope of the site of the ancient town. It differed in principle to the arrangement of the ensemble that stretched along the passage in the 14th century.

A bi-chamber mausoleum with high cupolas and a portal, facing the highway southwards, was erected on the south side of the lowest terrace. It is the mausoleum of a distinguished lady of the Timurids - "the Sultan's mother", of which fragments of the inscription of the portal affirm.

The "Octahedron", a new type of domeless mausoleum, was built, that was related to the central group of edifices. It was associated with the mausoleums (built with towers) of Western Iran and Azerbaijan. The part of it that remains comprises an eight-sided domeless pavilion with through pointed arches on the sides and a tomb under the floor. The form of the "Octahedron", that was most uncommon both to the Shahi Zindah ensemble and Samarkand as a whole, is probably identified with the masters of Azerbaijan, who were brought to the capital in Timur's time. Other mausoleums were built under Ulughbek. They were set open in the 1960s. They had a tomb of cross-shaped layout with a niche in the north behind the Unnamed-2 and others.

A fragment of facing made of coloured glazed and ceramic tiles. Turn of the 15th century

With the disintegration of the Timurid State at the close of the 15th century and accession of a new ruling dynasty - the Sheibanids of nomadic Uzbek stock - Samarkand was no more the capital, though it retained its importance as a political and cultural centre. In the 16th - 17th centuries work of monumental building in Central Asia was concentrated in the new capital city of Bukhara. Shahi Zindah, the Timurids' family graveyard, deteriorated by degrees. Nevertheless, small edifices for worship (sagane, small mosques and medressehs) appeared in the late Middle Ages and right up till the 19th century. The ensemble has come down to our days in a dilapidated condition. Soviet restorers, researchers, historians, archaeologists, architects and artists have studied and preserved this wonderful treasure-house of Central Asian architecture of the Middle Ages and restored it to life. It is a monument to the old masters, whose exceptional skill and talent are reproduced for ever in the masterpieces created by them. Shahi Zindah chiefly comprises small chamber structures. The volume, layout and transient construction of each edifice were the creative solution of architects who by no means repeated anything done before them. The chief merit of the ensemble is the diversity of methods of decorative facing. All the facing materials known in the East were used in the construction of the ensemble. On the monuments built in pre-Mongol times (mainly known as a result of excavations) one can behold magnificent pieces of carved terracotta and carving on wood and ganch, that brought fame to the Central Asian masters of the Middle Ages. The 14th - 15th century edifices represented all the known kinds of painted majolica, compositions of brick and Kashin (glazed tile based on silicate) majolica, multi-coloured painting on ganch with a great quantity of gilt, ganch and ceramic stalactite fillingin of niches, coloured glass trellis (panjara). All this imparts the Shahi Zindah ensemble with charm that is unequalled in the East. Interest in it has not declined to this day.

Glazed majolica in relief. A fragment of the facing. 14th century

A fragment of the decoration of Usto Alim Nesefi mausoleum. The stalactite band and brick mosaic. 14th century

A fragment of the facing of the portal of Usto Alim Nesefi mausoleum. Majolica in relief. 14th century

Mosaic border, made of a set of carved glazed tiles based on silicate. Turn of 15th century

A fragment of facing made of coloured glazed and ceramic tiles. Turn of the 15th century

Carved glazed terracotta. A detail of the facing. 14th century

A set of mosaic, made of glazed tiles based on silicate. A detail of the facing. Close of 14th - turn of 15th centuries

Carved glazed terracotta. 14th century

Carved glazed terracotta. 14th century

Carving on marble. A detail of the facing of the tombstone. 14th century

Wood carving. A fragment of a door. Turn of the 15th century

A mosaic medallion on a panel of hexahedral slabs. The first half of the 15th century

A fragment of facing in the technique of the sets of mosaic made of glazed tiles based on silicate

A fragment of facing of the turn of the 14th century. Sets of mosaica compiled of glazed tiles based on silicate

А fragment of facing of the turn of the 15th century Sets of mosaic made of glazed tiles based on silicate

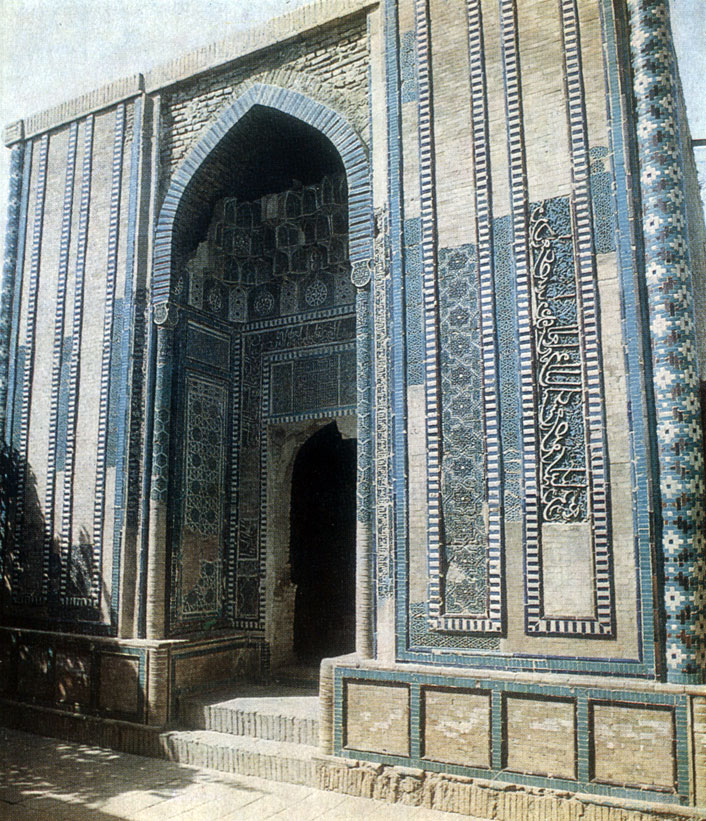

The main portal at the entrance to the ensemble. 1434 - 1435

The staircase of the 'lower group' of buildings in the ensemble. The southern slope of Afrasiab

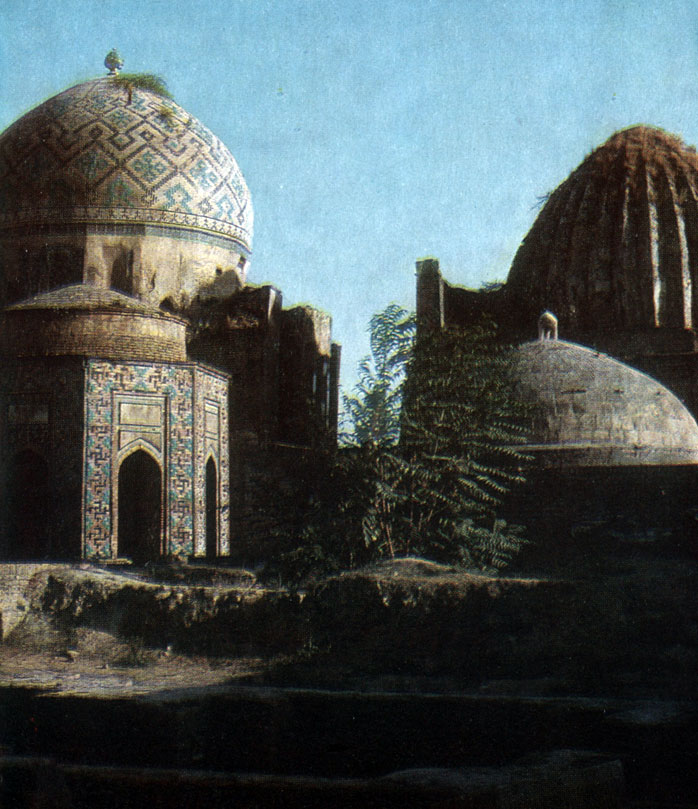

A bi-cupola burial vault of the 'lower group' of buildings and a 14th century mausoleum on the crest of the wall

A 14th century mausoleum on the wall in Afrasiab

A bi-cupola burial vault of the 'lower group' of buildings and a 14th century mausoleum on the crest of the wall

A bi-cupola burial vault of the 'lower group' of buildings. Early 15th centrury

The base of a cupola - a round drum - ziaratkhana (a chamber for worship) of a bi-cupola mausoleum

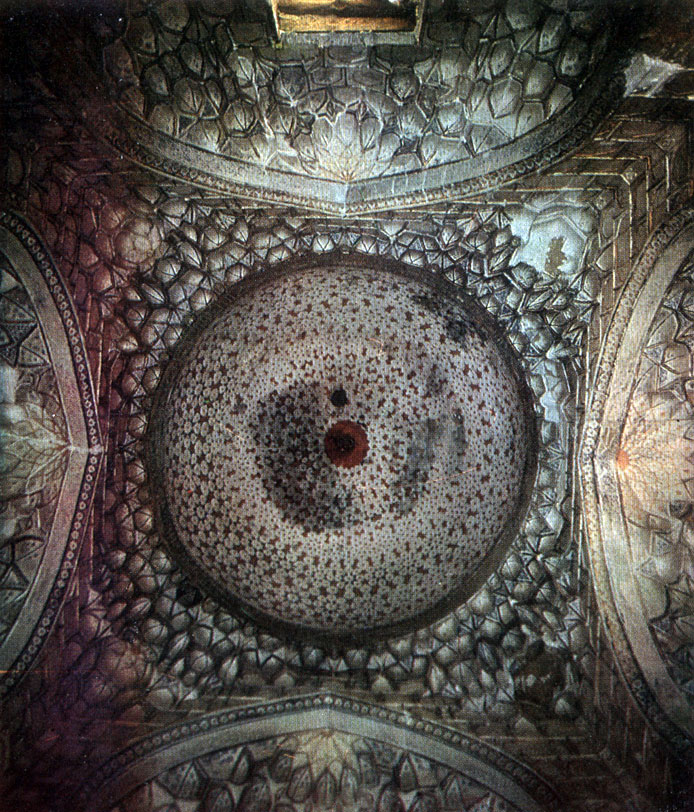

A stalactite cupola made of ganch in a gurkhana (a burial chamber) of a bi-cupola mausoleum of the 'lower group' of buildings

A group of 14th century mausoleums on the crest of the wall in Afrasiab

14th century burial vaults on the crest of the wall in Afrasiab, in the centre - the second chartak

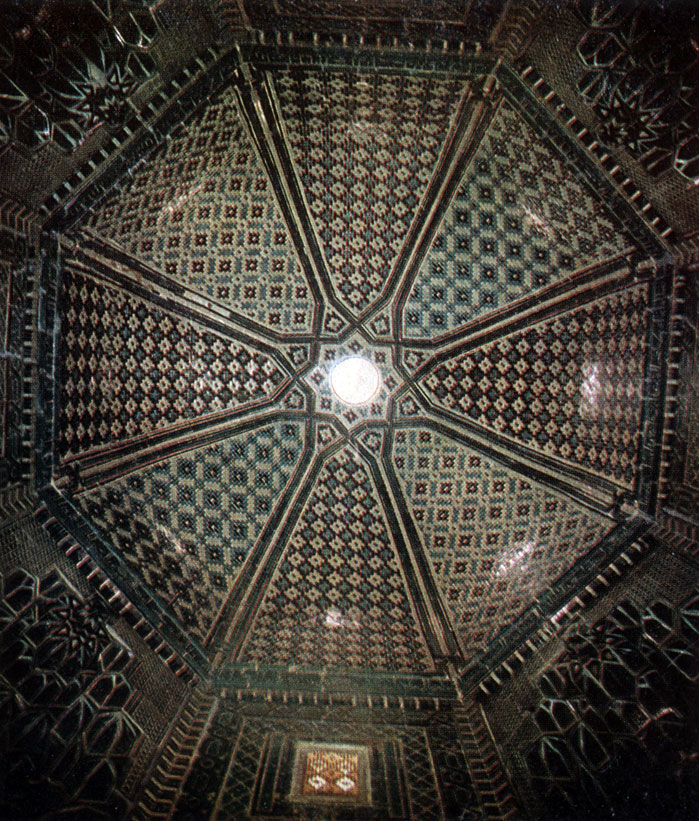

The inner cupola of Shirinbek-aka mausoleum. Painting on ganch plaster

A group of 14th century mausoleums on the wall in Afrasiab

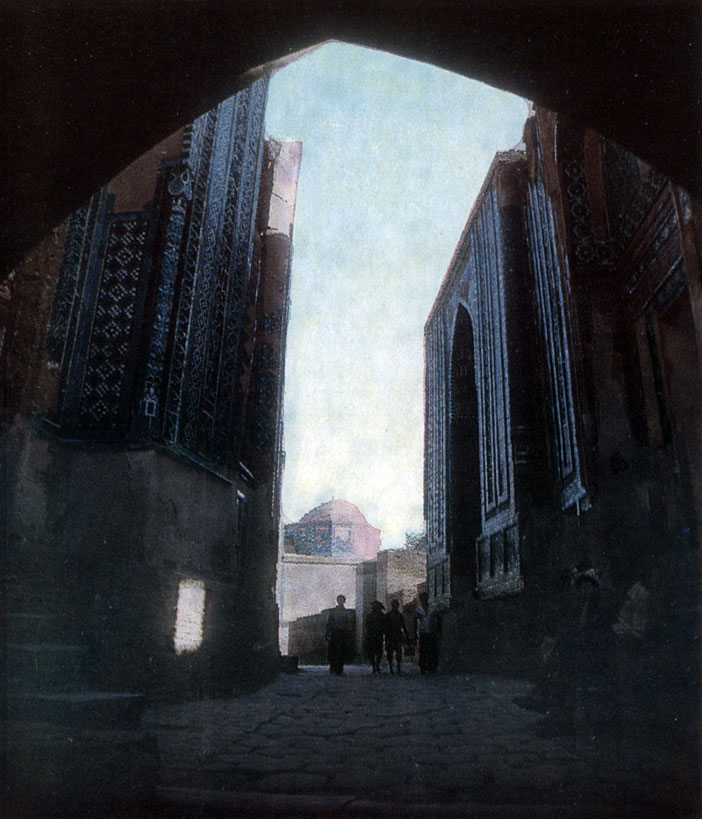

A corridor in the central part of the ensemble. A view from the north

A general view of Shahi-Zindah ensemble. A view from the south-east

Mausoleums of the 'central group' of buildings. 14th - 15th centuries

Tuglu-Tekin mausoleum (or Emir Khussein). 1376

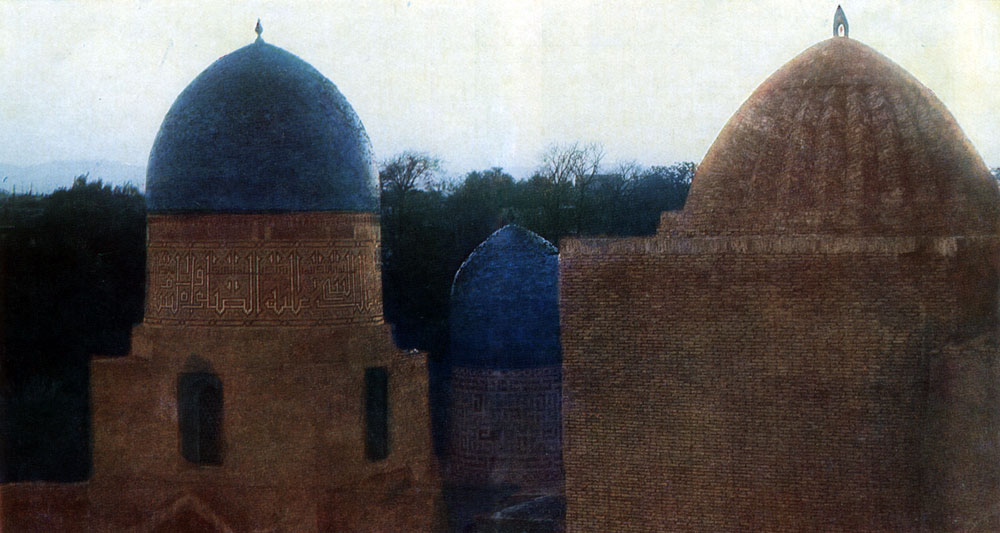

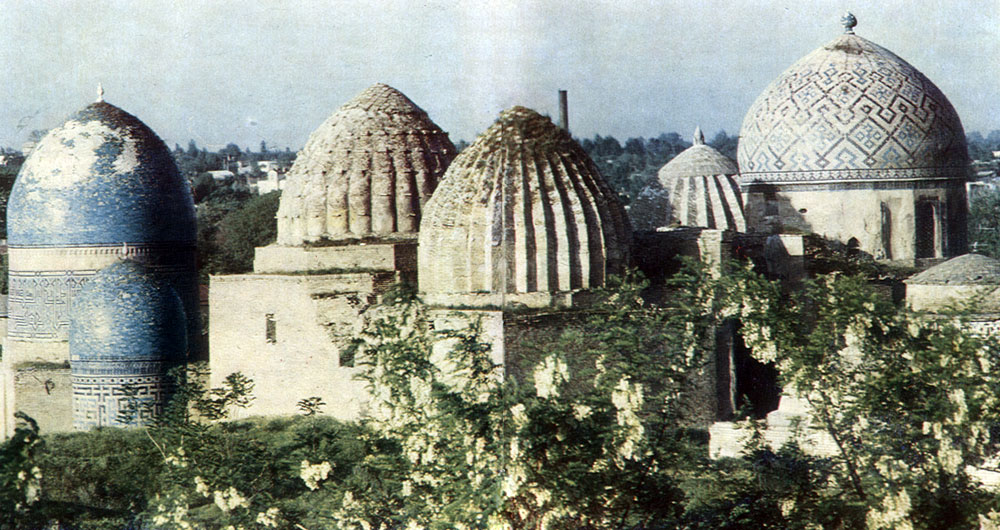

Cupolas of mausoleums of the 'central group' of buildings

Cupolas of Nth - 15th century burial vaults

14th century mausoleums. In the foreground - mausoleums of the work of Usto Alim Nesefi or Unnamed-1. The 1380s

Mausoleums of the 'central group' of buildings. In the foreground - Unnamed-1

The 'upper group' of monuments. On the left - Tuman-aka mausoleum and mosque. 1405

The upper and central groups of monuments. A view from the north-west

On the left - Tuman-aka mausoleum, on the right - Emir Burunduk mausoleum. The 1390s

Ribbed cupolas of mausoleums of the 'central group' of buildings. On the left - Shadi-Mulk-aka mausoleum, 1372; on the right - Emir-Zade mausoleum. 1386

Monuments on the crest of the wall in Afrasiab

A general view of Shahi-Zindah ensemble. A view from the west

Shahi-Zindah ensemble. A view from the west

The 'central group' of mausoleums, in the foreground - Unnamed-1. It was built by Usto Alim Nesefi. The 1380s

The 'central group' of mausoleums. A view from the corridor from the north

Cupolas of mausoleums at the fortress wall in Afrasiab

The entrance portal of Emir-Zade mausoleum from the niche of the 'Octahedron'

The interior of the ' 'Оctahedron'. 15th century

The 'central group' of mausoleums. On the right in the foreground - Unnamed-2

The north entrance to Tuman-aka mosque. 1405

Cupolas of mausoleums of the 'central group' of buildings

A corridor of the ensemble at the fortress wall in Afrasiab. On the left - the 'Octahedron', on the right - Shadi-Mulk-aka mausoleum. 1372

A corridor of the ensemble. A view from the south

Cupolas of mausoleums of the 'central group' of buildings

A corridor of the ensemble seen from the arch of the second chartak

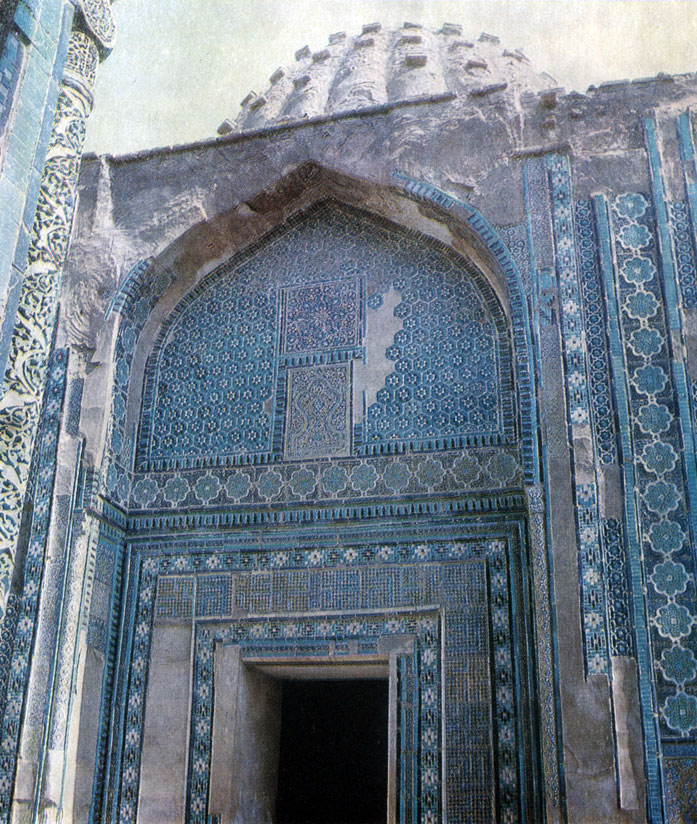

The main faсade of Emir-Zade mausoleum. 788 hijra - 1385 A. D

A corridor of the ensemble. A view from the south

A portal niche of Shirinbek-aka mausoleum. 787 hijra - 1385 A. D

On the left - the 'Octahedron' and Shirinbek-aka mausoleum

The corridor of the 'central part' of the ensemble. A view from the north

A corridor of the ensemble at the second chartak

Emir Burunduk mausoleum. The west and south faсades

A general view of a corridor of the ensemble. A view from the north

Tuman-aka mausoleum. On the left - the upper rotunda of an 11th century minaret (a tower used for summoning Moslems to prayer)

On the left - Shirinbek-aka mausoleum

The 'upper group' of buildings. On the left - Tuman-aka mausoleum

A corridor of the ensemble. A view from the north

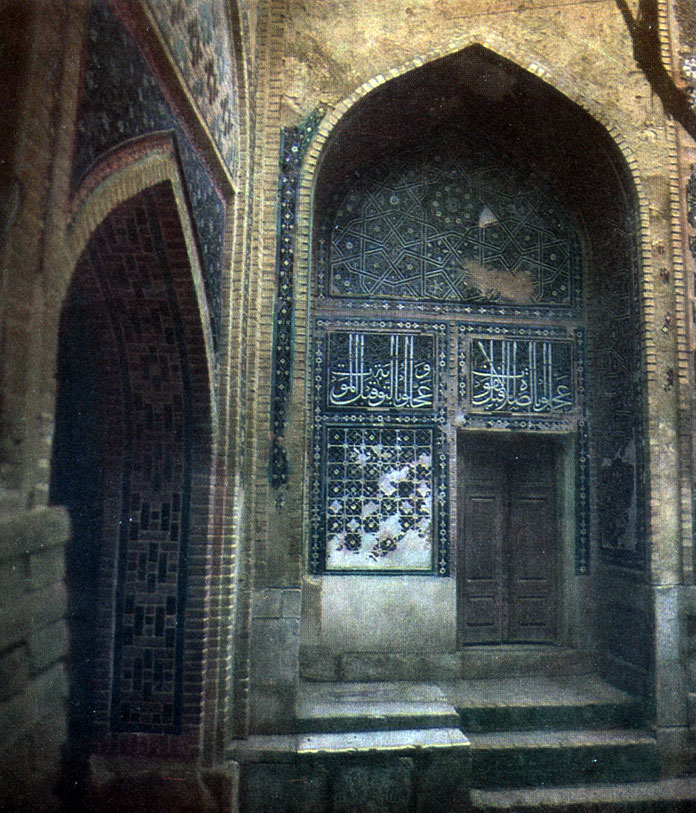

A portal niche of a mausoleum. 1361

A corridor of the ensemble, viewed from the third chartak

The interior of Shirinbek-aka mausoleum

A corner sub-cupola niche, filled with decorative and ceramic stalactites. A ziaratkhana of Kusam ib n Abbas ensemble

A ceramic majolica tombstone of the 1380s from the Kusam ibn Abbas gurkhana. On the end face - the date of Kusam's death - 57 hijra - 676/677 A. D

A mid-14th century ceramic tombstone from an unearthed mausoleum

A ceramic majolica panel from mausoleum of Emir Burunduk 1390s

The inner cupola of a ziaratkhana of Kusam ibn Abbas ensemble. Glazed ceramics. Restored in the 1960s

A wooden panjara (lattice). 14th century. From Kusam ibn Abbas ensemble

A carved wooden door of the third chartak in Kusam ibn Abbas ensemble. Carved by Ytisuf Shirazi. 807 hijra - 1404 - 1405 A. D

A fragment of a carved wooden door. 1404 - 1405

A fragment of a carved wooden door. 1404 - 1405

A fragment of a carved wooden door. 1404 - 1405

A fragment of early 15th century facing. A set of inlaid work of glazed tiles based оn siсicate

The rnd face of a carved marble tombstone with an epitaph and the date 758 hijra - 1357 A. D. (in the wall of the third chartak)

The base of an 11th century minaret of Kusam ibn Abbas ensemble

A fragment of 14th century carved marble tombstone

The 'upper group' of monument. On the right - Kusam ibn Abbas ensemble. 11th - 19th centuries

The main faсade of the mausoleum. 1361

The 'upper group' of monuments or the north courtyard. A view from the arch of the third chartak

The inner cupola of Tuman-aka mausoleum

Стропы канатные двухветвевые http://komplektacya.ru/gruzopodjemnoe-oborudovanie/stropy-gruzovye/stalnye/2sk/strop-2sk

|

|

При копировании обязательна установка активной ссылки:

http://townevolution.ru/ 'История архитектуры и градостоительства'